Why does an obscuring mask of dirt and grime increase the value of old furniture but decrease the value of old paintings? Is it curious to anyone else that appraisers always recommend cleaning paintings and jewelry, even rugs, so that we can enjoy the detail; but want to see the same dirt, cigarette smoke, and general grudge left on beautiful wood?

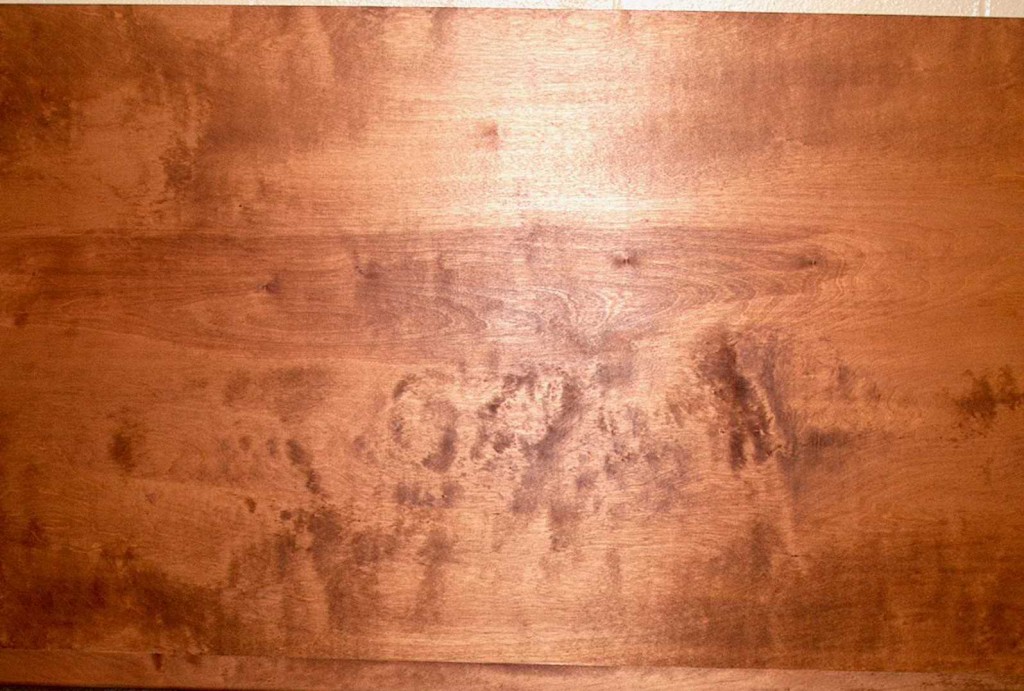

The beauty of wood furniture and gifts is a combination of several ingredients: the overall design – combination of straight lines and curves, shapes and proportions; woodworking – joinery used, execution skill; and artistry – the wood’s color, grain pattern, character and figure created by Nature, how the grain patterns are used, how the boards are sequenced and combined, and sometimes how different woods are combined. A mask of dirt and grime obscure both the woodworking and the artistry.

An admired painting invites closer attention to details – how the major components are spatially arranged, how each component interacts with the others, the amount of detail used for each component, how colors and brush strokes are layered, and so on. The effect is to draw your attention to finer and finer detail, and each time you do so you are rewarded visually and emotionally. When new, antique furniture offered the same ongoing pleasure for its owner.

Some boards have little or no character – use them for the bottom and back. Others have strong oval and arch grain patterns that would visually detract from interplay of components and overall design, or from the style - again, use them only in appropriate styles and then in visual balance. When one looks below the dirt and grime on magnificient antiques, we’ll see those were the practices of the skilled craftspeople who built them.

Perhaps someday it will be possible to clean furniture, as one would clean a dirty painting, without losing most of its appraised value.