When a dye, pigment stain or oil is wiped onto raw hardwood, the wood can develop an uneven color.

Many people would find this picture of maple, found on the Internet, to be stunningly beautiful. The displayed figure is known as curly, tiger or fiddleback. (It’s not known, and really not important, if the picture shows solid wood or maple plywood.)

Many people would find this picture of maple, found on the Internet, to be stunningly beautiful. The displayed figure is known as curly, tiger or fiddleback. (It’s not known, and really not important, if the picture shows solid wood or maple plywood.)

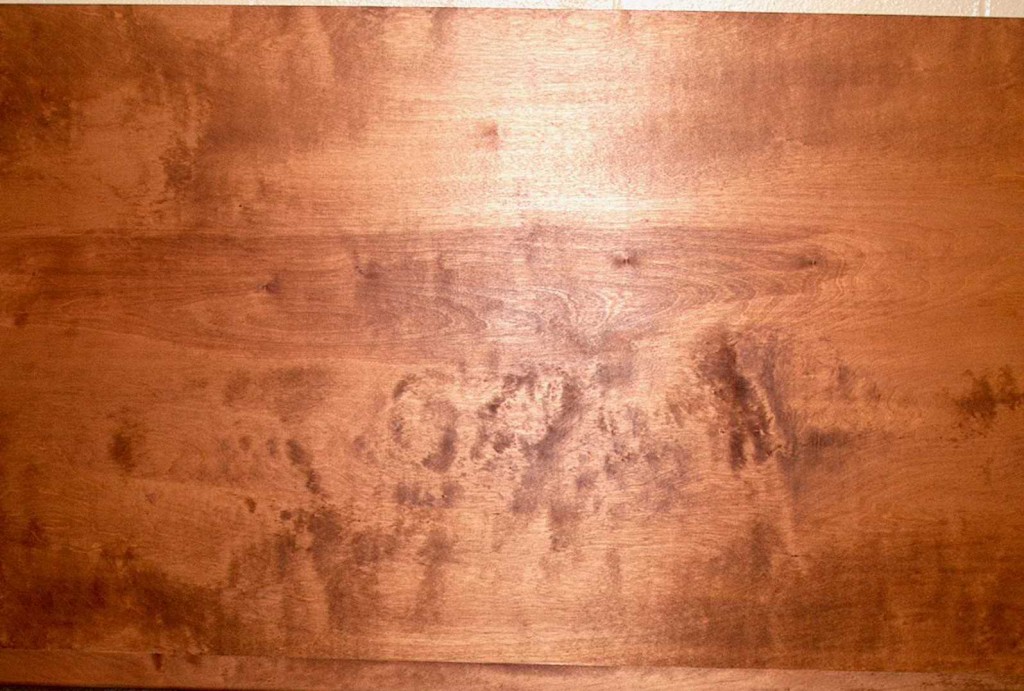

Like the above maple, this birch plywood shows lighter and darker areas (in addition to the band of darker heartwood in the middle of the picture). This figure is known as blotch. (After a water based dye was wiped on and dried, three coats of an oil-varnish blend were wiped on.)

Like the above maple, this birch plywood shows lighter and darker areas (in addition to the band of darker heartwood in the middle of the picture). This figure is known as blotch. (After a water based dye was wiped on and dried, three coats of an oil-varnish blend were wiped on.)

Like many hardwoods, maple can show blotchy figure, and birch can show curly figure, both as solid wood and as the surface veneer of hardwood plywood.

In both pictures, the light and dark areas are due to the wood’s having an uneven rate of absorption – the darker areas absorb more color and/or oil. Although they were probably different in these two pictures, it is possible that a similar sequence of color and finishing steps were applied to the maple and birch.

When the uneven rate of absorption is very regular, as in the first picture, many will say the finisher was especially skilled. When the uneven rate of absorption is irregular, as in the second picture, some will say the finisher was unskilled. Both pictures show the natural response of hardwood to wiped color and/or oil.