Shaker Nesting Oval Boxes

(Following a brief introduction to making Shaker oval boxes is an extensive annotated collection of photos of original Shaker boxes.)

Oval nesting boxes are one of the most widely recognized symbols of Shaker society and Shaker woodworking. Technically ellipses, they are as beautiful as they are functional.

Light but strong, they also represent some of the best traditions of Shaker work. Like the Shakers' products, these are individually handcrafted to the highest standards and highlight the beauty and character of wood. They are graceful and useful, and can be a treasured gift as well as an attractive keepsake box.

The shape of Shaker oval boxes invites you to pick them up and hold them. The extensive handcrafting of these boxes is readily apparent and rewarding when you look closely at the details.

Although many sources mass produce oval boxes, these are individually marked out, drilled and cut to maintain the exactness of curve on each box. After bending and tacking, the boxes are strictly hand sanded to maintain the crisp angles and cuts. The labor time is dramatically increased, but the results are distinctive.

For the greatest strength and longevity, the lids and bottoms are 1/4" baltic birch plywood, the best grade available. Both sides are covered in the workshop with the best grade of quartersliced bookmatched cherry veneer. This also adds significantly to the investment in time, but the objective is to make the highest quality Shaker oval boxes possible.

Most often the Shakers made a container with matching lid; less frequently they made a container with a fixed handle or an oval box with a swing or pivoting handle.

Fabric lining can be added to any oval box to make it more functional. A fabric lining may also be desired when gifting an oval box as a keepsake treasury.

Description

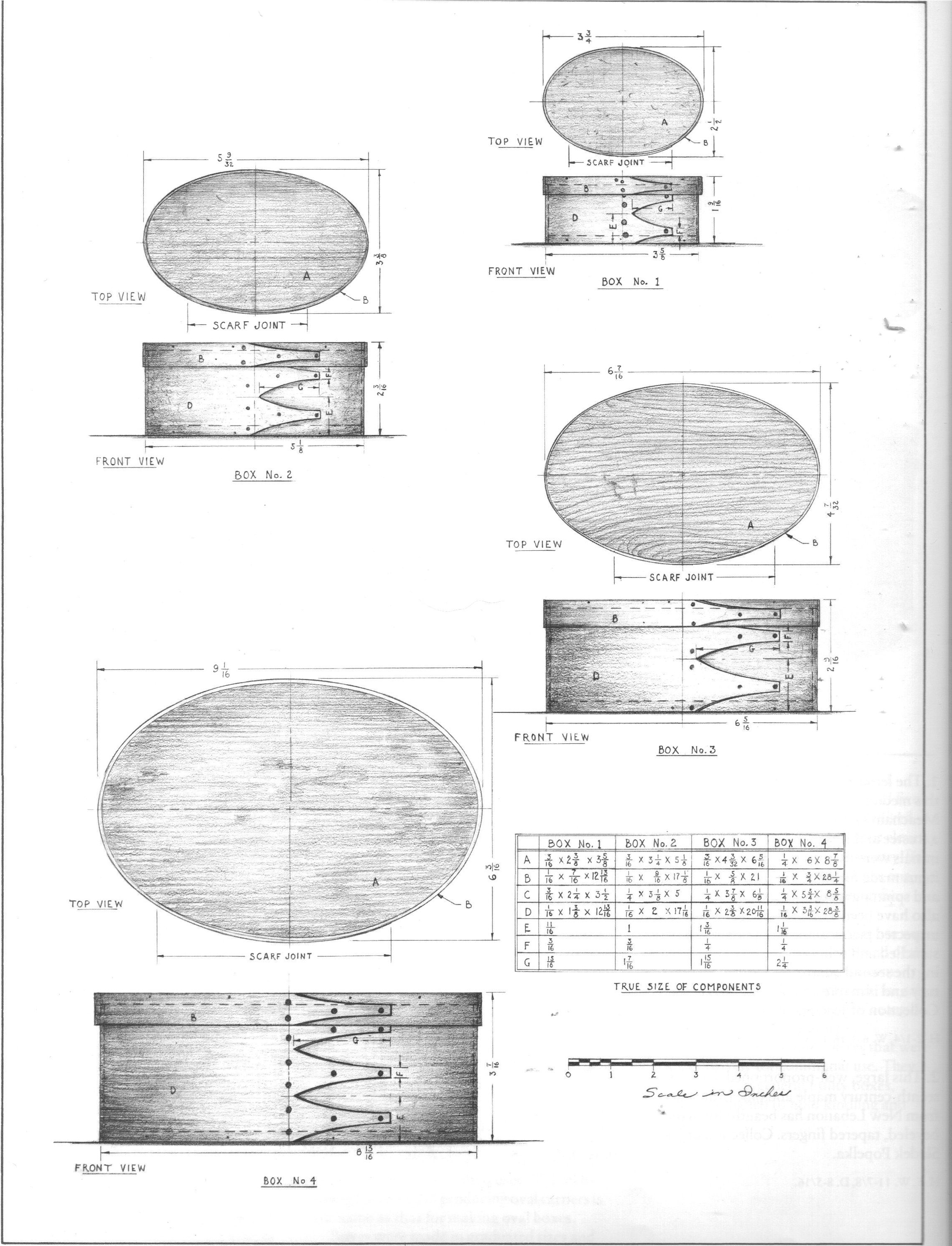

These boxes are reproductions of authentic Shaker oval boxes whose measurements were recorded and published by Ejner Handberg in Shop Drawings of Shaker Furniture and Woodenware Vol I, pages 62-70.

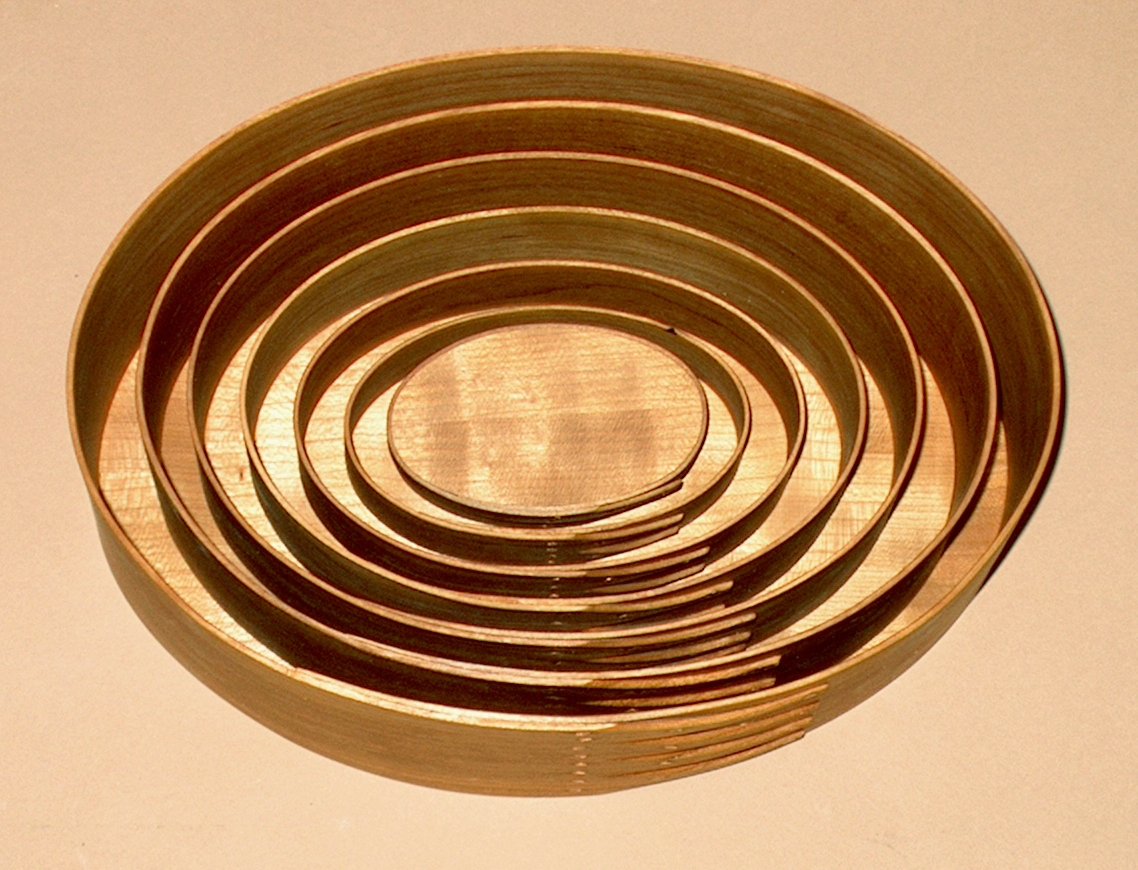

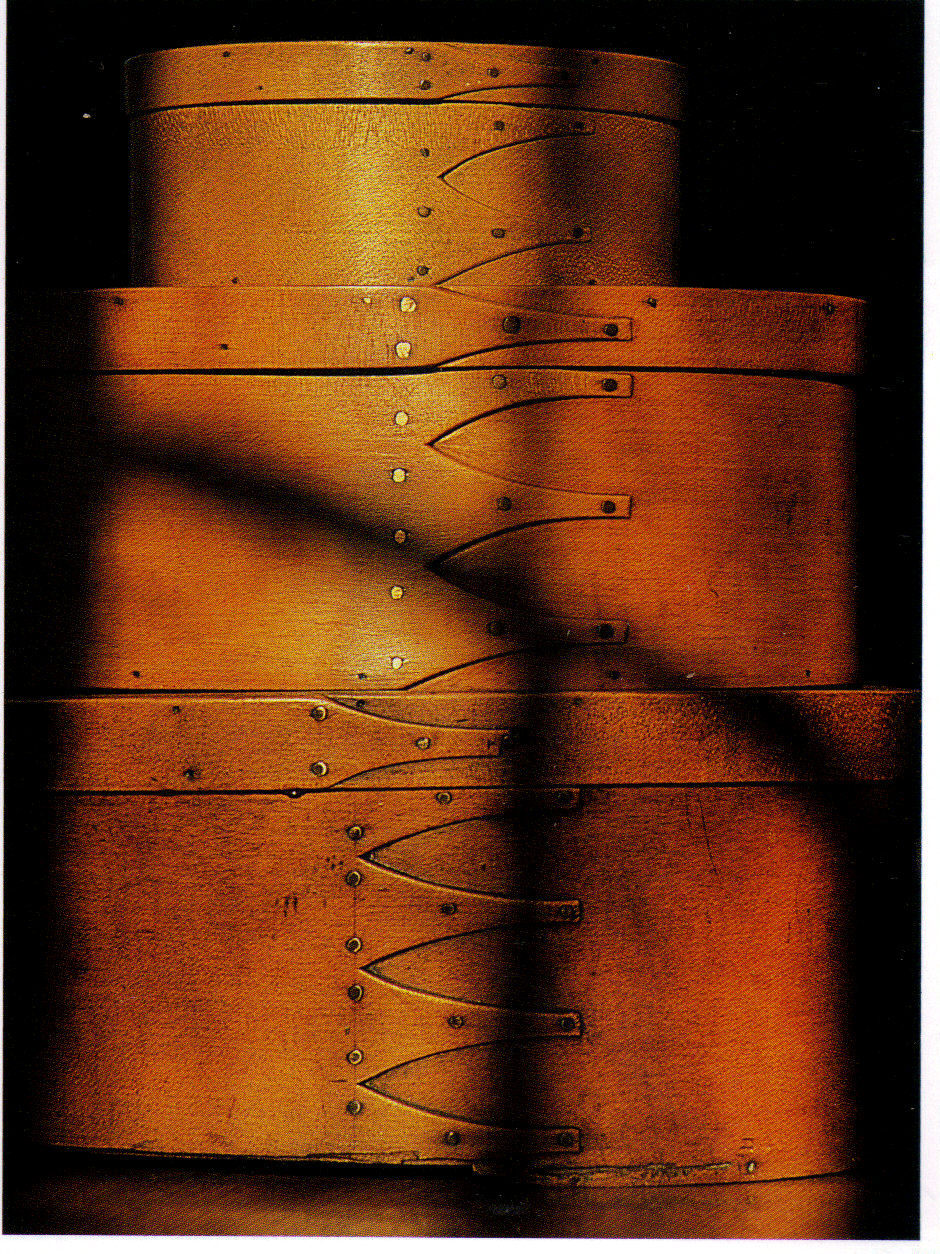

Here is the same set of seven oval boxes, nested one inside the other. Only the #0 has its lid.

Using a numbering system arbitrarily assigned by Handberg, they range in size from a #1, approximately 4 7/8” x 3” x 1 ¾”H, to a #6, approximately 11 ¼” x 8 ¼” x 4 9/16”H. Also included is a #0, approximately 3 ¾” x 2 3/8” x 1 ¼”H, designed by John Wilson as an extension to Handberg’s set. (More information on John Wilson appears below.)

For ease of communication, consider each oval box to be a container and a lid. The container has a wide band pegged to a bottom. The lid has a narrow band pegged to a top.

Each band is bent back on itself, so that one end is overlapped by the other. To avoid a thick step at the start of the overlap, the inner end is tapered or “feathered.”

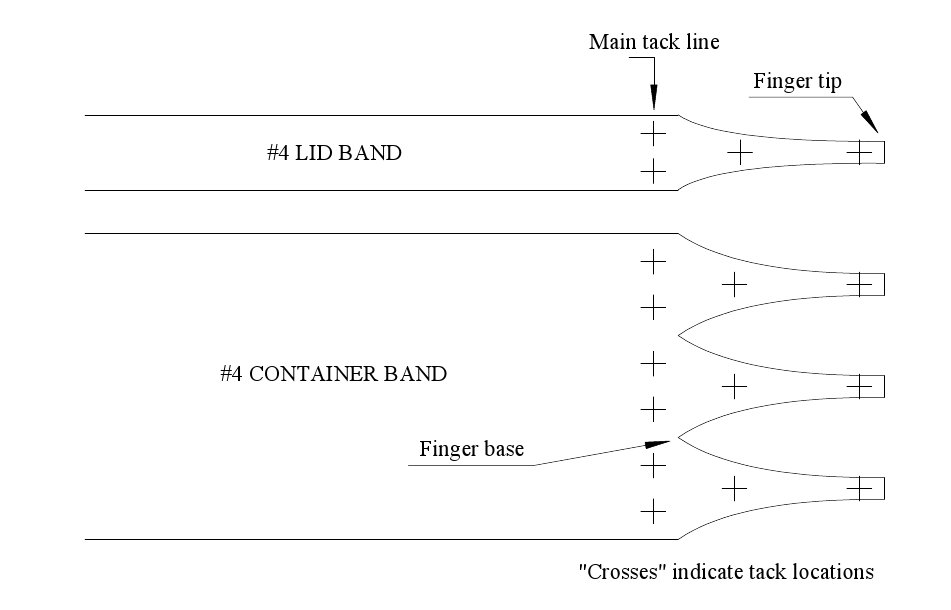

Each lid band has a single finger and four tacks. Each container band has two or more fingers and four tacks for each finger. There are single tacks in the tip and middle of each finger, and a main tack line just beyond the base of the fingers.

The finger shape sometimes is called a swallow tail.

All of the lid bands have a single finger, so the similarity between boxes is pronounced. As the box size increases, the lid band finger is wider and longer, but the profile is consistent.

When the just bent boxes are dried, care is taken so keep the main tack lines in the middle of the lid and container, so that they are aligned.

These details are important elements of the sophisticated visual appeal of a stacked set of boxes.

The bands are solid cherry. After tracing the finger pattern and tack locations from a pattern, the bulk of the wood between the fingers is cut on a band or scroll saw. The tack holes are made using the drill press. The other end is feathered on a power sander for a smoother overlap when the bands are bent.

After ten minutes in hot water to soften the wood, the fingers are trimmed to final shape by hand. After another twenty minutes in hot water, the bands are bent by hand around a solid wood elliptical form or core and the tacks driven. The bent bands then dry for forty-eight hours on elliptical shapers.

Offering far greater strength and stability, the lids and bottoms are baltic birch plywood veneered by me with premium quarter sliced cherry veneer. Even quartersawn pine used by the Shakers will expand and contract seasonally, which may explain why so few Shaker-made boxes remain.

The plywood lids and bottoms are custom fit to each band. Because premium quartersliced cherry veneer is bookmatched to both faces of the baltic birch plywood, both surfaces of the lids and bottoms are striking.

Finishing begins with a careful but complete hand sanding with 150 and then 220 grit sandpaper. A coat of oil-varnish blend is thoroughly rubbed into the surface and allowed to dry. Perhaps because the bands are bent, the first coat of finish raises the grain in places. A second detailed hand sanding using 220 and 320 grit leaves the surface pleasingly smooth. A second coat of oil-varnish blend is hand rubbed and allowed to dry thoroughly for a protective in-the-wood finish that brings out the unique warmth and character of the wood.

Developing The Finger Templates and Handle Forms

Extensive hand work was a key ingredient for the sculpted grace of the Shakers’ boxes as well as for these reproductions. Such hand work means the final shape of the fingers varies slightly from box to box, and even between fingers on a box, but has character and charm lacking in mass produced boxes made with machine cut fingers.

The Shakers used tin patterns or templates for each size box to draw the shapes of the fingers. Because the Shakers believed the quality of their work was a reflection of the depth of their religious commitment, they would have carefully made exact and very consistent patterns.

As Handberg’s measurements were taken from finished boxes, they incorporate the uniqueness of handcrafted pieces rather than the exactness of the Shakers’ patterns. Also, the Shaker-made oval boxes Handberg studied may in fact have been made by more than one individual over a span of years or decades.

To honor the spirit of the Shakers, I made careful measurements of various landmarks of the Handberg drawings. These measurements were then studied at length to determine the underlying design progressions the Shakers almost certainly incorporated.

For each container and lid, several very slightly different curves were drawn and evaluated to find one both pleasing to the eye and aligned with the Handberg drawing.

Finally, all of the individual patterns were compared to each other to confirm that there was a consistent shape and transition between box sizes.

Fixed and swing handles can be of several different types of curve, depending on personal preference. Common shapes or forms are bonnet, arch, and ellipse.

Bending forms were made for each of the three types to fit a #5 oval box. The bonnet had I think a 2 1/2" radius at the corners; the ellipse was a slightly larger tracing of a #5 lid; and the arch was in between the two. Of the three, it was felt the arch, shown here, clearly was the most graceful and attractive.

Examples of these handle forms on authentic Shaker oval boxes are presented below.

Shaker Production of Oval Boxes

The first Shaker-made oval box was produced in the 1790’s in either Watervliet or New Lebanon, New York. (Making Authentic Shaker Furniture by John Shea, page 60) One of the most prolific Shaker box makers and the last Shaker Brother, Delmar Wilson, made his last oval box in 1955 at Sabbathday Lake, Maine. (By Shaker Hands, June Sprigg, page 189)

At the time the Shakers were becoming established, round boxes were made in any number of countries. The first Shaker box, though, was "oval". Perhaps it fit better on shelves, perhaps the first maker preferred the elliptical shape over round, . . . We may never know exactly why the Shakers mainly built oval boxes.

Most of the early Shaker oval boxes were made for their own use as storage containers. Contents included tea, herbs, spices, sewing supplies, and perhaps small tools, nails, tacks, and screws.

Oval boxes were made at most Shaker communities. Commercial production occurred mainly in Maine, New Hampshire, and at Mt. Lebanon, New York. (The Shaker Legacy, Christian Becksvoort, page 219) In 1836 at Mt. Lebanon, 3500 boxes were produced. Between 1822 and 1836, inclusive, some 24,250 oval boxes were made at Mt. Lebanon. (Shaker Style: Form, Function, and Furniture, Sharon Koomler, pages 111-112)

Technically, the Shaker “oval” boxes are ellipses. An oval has semi-circular ends connected by straight lines. An ellipse is an entirely different shape; nonetheless, the boxes are always referred to as oval, and will be here as well.

An ellipse has major and minor axes perpendicular to each other. If the ratio of their lengths is 1, the ellipse is a circle. As the ratio increases the ellipse becomes more elongated.

The boxes documented by Handberg have an average ratio of about 1.5 (1.78, 1.64, 1.56, 1.50, 1.46, and 1.45). Perhaps the Shakers found through experience that the boxes nested better with a slightly decreasing ratio. In addition, the minor axis essentially increases by 1” starting at 2 ½”. (Handberg’s smallest box actually has a minor axis of 2 9/16” but it could have been slightly wider by accident for any of several reasons such as a slightly thicker than intended veneer, the band accidentally expanded slightly before the first tack was clinched, and so on. Therefore I’ve adjusted the interior dimensions of the #1 oval box to 4 7/16” x 2 8/16” with a ratio of 1.78.)

There was not one set of standard sizes made across all Shaker communities. Even Handberg’s six may have been part of a larger standard set.

(The following two quotes are from a study specifically of the Mt. Lebanon Shaker community, and may or may not apply equally well to other communities.)

"It was common to sell [the oval boxes] in nests, a nest consisting at first of 12 boxes, then of nine, and at a later date of seven and five." (The Community Industries of the Shakers, Edward Deming Andrews, page 161) It wasn't made clear whether at any time a nest could have been a subset of the total number of sizes offered for sale.

"By 1834 oval boxes were sold by number. The largest sizes, Nos. 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5, were the most popular." (The Community Industries of the Shakers, Edward Deming Andrews, page 163)

Even within one community, the sizes of oval boxes may have evolved over time. A catastrophe such as a fire or storm might have destroyed all the patterns and forms at a community. Given their constant search for improved furniture forms, a community may have decided to create a new, different set of patterns and forms to improve their product. And when a new Shaker community arose they were as likely to make their own patterns and forms as they were to purchase them from an existing community. Shaker woodworkers did not create and save working drawings of furniture, and there is no mention in reference books of drawings or measurements of oval boxes being recorded or shared between communities.

These careful drawings from The Book of Shaker Furniture, John Kassay, page 20, show some of the differences in Shaker made oval boxes. All four of these boxes are attributed to eastern communities during the nineteenth century.

On the upper right box the main tack line is on the centerline of the minor axis, the main tack line is slightly distant from the base of the fingers, and the fingers lack intermediate tacks. The upper left box has the main tack line to the left of the centerline of the minor axis, the main tack line is even more removed from the base of the fingers, and the bottom edge of the bottom finger extends beyond the base of the other fingers back to the main tack line. The lower right box has the main tack line to the right of the centerline of the minor axis and close to the base of the fingers. On the lower left box the main tack line is on the centerline of the minor axis and is close to the base of the fingers.

The majority of Shaker-made oval boxes used maple for the bands and quartersawn pine for the lids and bottoms. Less often, the bands were made of birch, cherry, and oak. Like early Shaker furniture, for many years the oval boxes were painted. Yellow, green, blue, and red were the most common colors. (The Book of Shaker Furniture, John Kassay, page 18)

As the number of Believers continued to decline, Shaker communities had more difficulty maintaining their way of life. It became increasingly necessary to purchase goods and supplies from the World, so income from sales of Shaker-made items such as oval boxes became more important. “In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many carriers were padded and lined with pretty silks or satins and outfitted with sewing accouterments, designed to be sold in Shaker stores. Typical accessories included a pin cushion, a cake of beeswax, an emery, and a needle case. These were attached to the box with ribbons that were looped and tied through small holes in the box.” (Shaker Style: Form, Function, and Furniture, Sharon Koomler, page 112)

This picture from page 60 of Making Authentic Shaker Furniture by John Shea is one of those Sabbathday Lake boxes made by Brother Delmar Wilson.

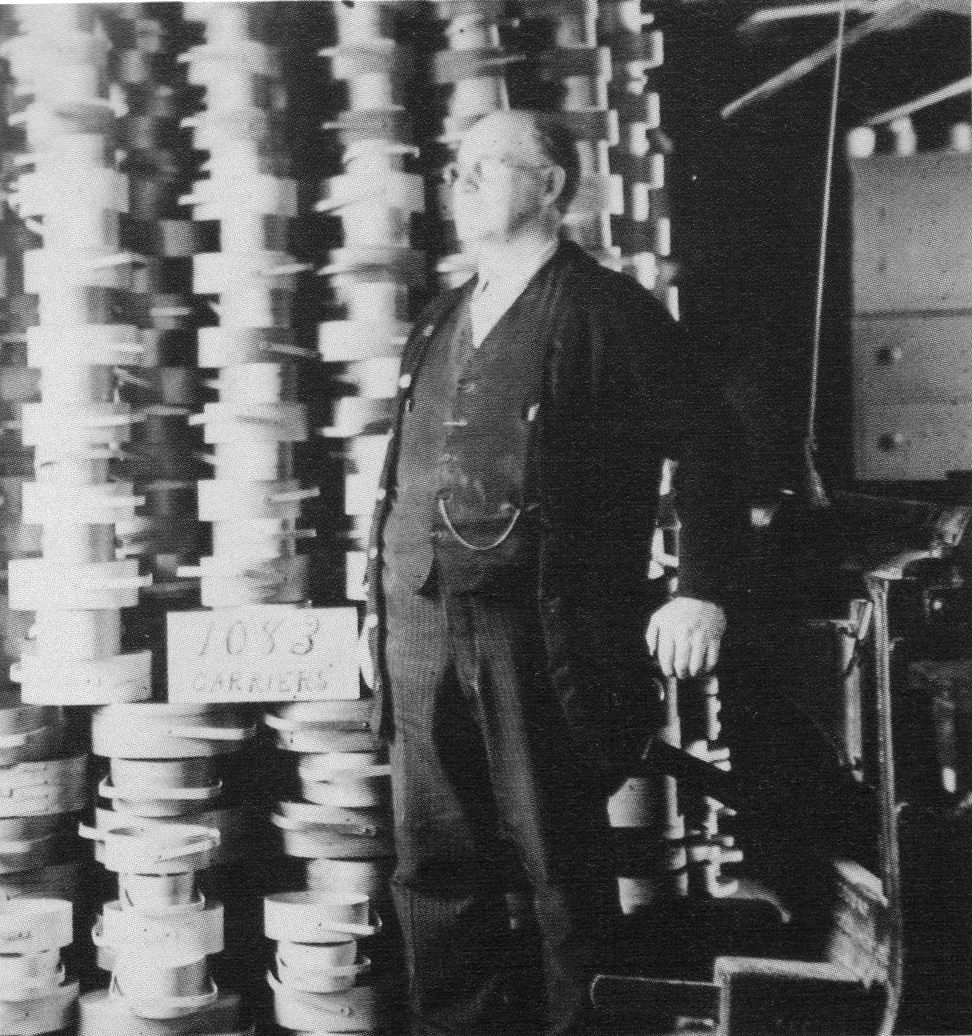

This may be one of the most often seen photos on the subject of Shaker oval boxes. It shows Brother Delmar Wilson at Sabbathday Lake with the result of one winter's work. The handles all appear to have a bonnet shape with no formed neck. (Shaker Style: Form, Function, and Furniture by Sharon Duncan Koomler, page 114)

Based on recollections of Brother Delmar Wilson, the first lined sewing carriers were made at Sabbathday Lake in 1894. Sisters Amanda Stickney and Sirena Douglas lined two Mt. Lebanon carriers that had been given to them, and sold them at a resort at nearby Poland Springs. At first Sabbathday Lake continued to line on-hand spare boxes. In 1896 Brother Wilson made 30 round carriers which were lined and sold. In 1897 he made his first oval carriers to be lined as sewing carriers. (From Shaker Lands and Shaker Hands, Stephen Miller, page 123)

This picture is one of Brother Wilson's 1896 round carriers. (From Shaker Lands and Shaker Hands, Stephan Miller, page 123)

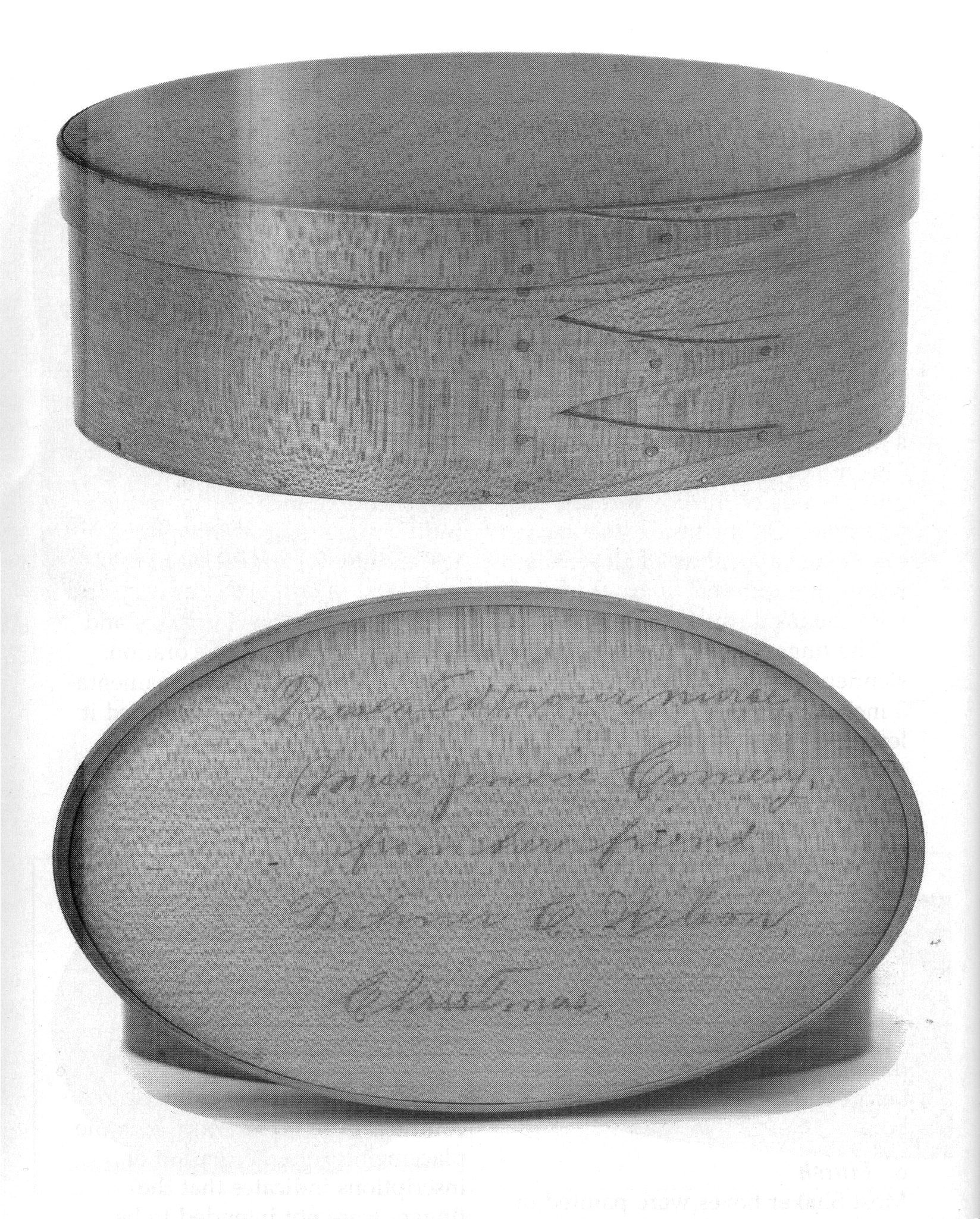

Here is the first of two oval boxes definitively attributed to Delmar Wilson. It is made using figured maple throughout. The tacks on the main tack line are equidistant, rather than grouped at the bases of the fingers. The lid and bottom are secured not with wooden pegs commonly used today but with copper points, much like headless nails, more common on early Shaker oval boxes. (Shaker Woodenware: A Field Guide Volume 1, June Sprigg and Jim Johnson, page 42) At 6 15/16" x 4 3/16" x 2 6/16"H, the box is very similar in size to Handberg's #3, 7" X 4 8/16" X 2 8/16"H.

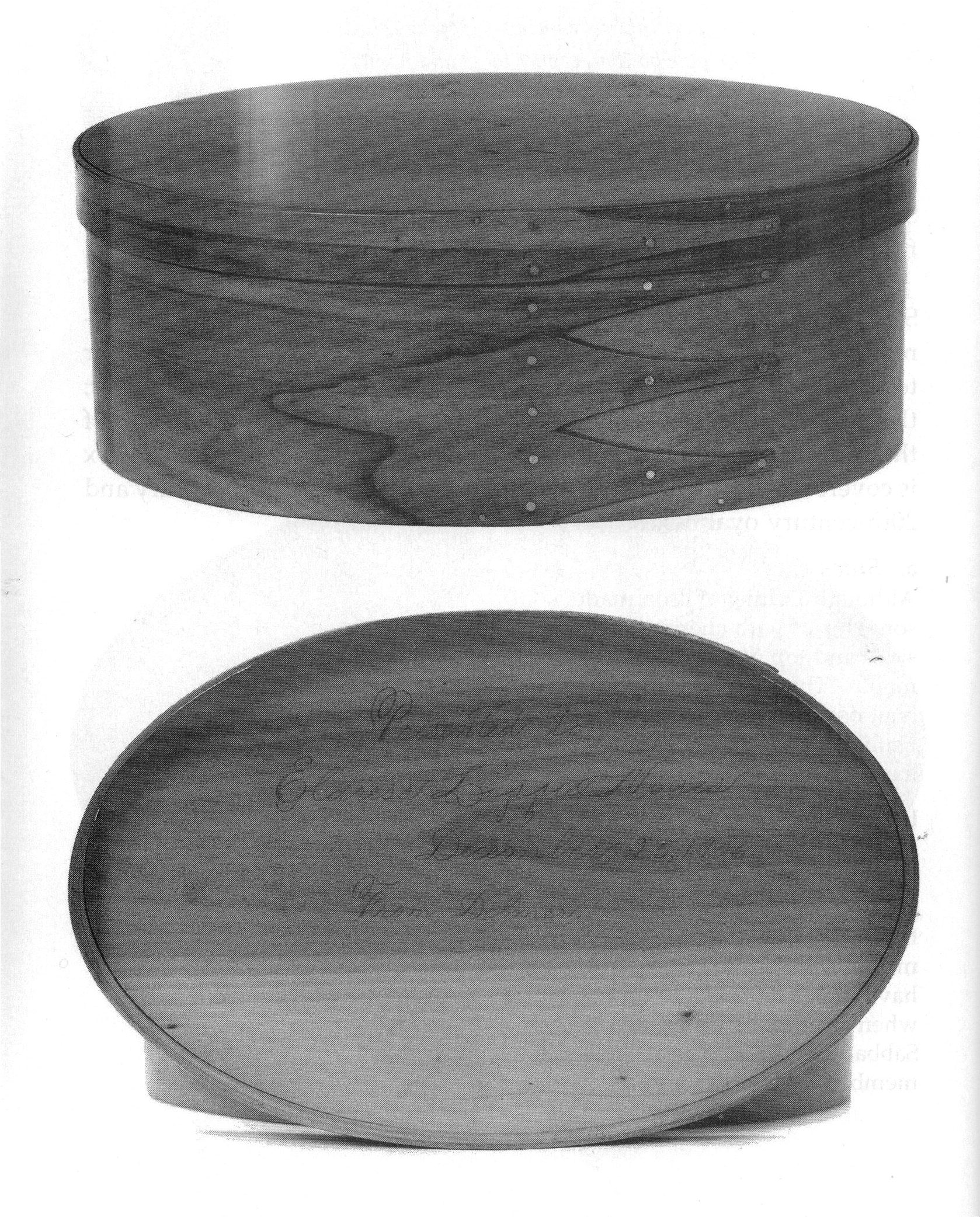

Here is the second of two oval boxes definitively attributed to Delmar Wilson. It has red gum top and sides, and a pine bottom. Main line tack placement and use of points is like that on the prior example. (Shaker Woodenware: A Field Guide Volume 1, June Sprigg and Jim Johnson, page 44) At 8 3/16" x 5 8/16" x 3 1/16"H, this box is very similar in size to Handberg's #4, 8 4/16" x 5 8/16" x 3 1/16"H.

One difference between these two Wilson boxes and the two measured by Handberg is the width increment, 1 5/16" for these two boxes and 1" for the Handberg measurements. Nested sets seem to have almost exactly 1" between pairs of boxes. Perhaps Wilson's were intended strictly for use as swing handled lined sewing boxes, where there would be no need for nesting.

Sabbathday Lake and Alfred are the Shaker communities mentioned as having made lined sewing boxes. But in the 1920's and early 1930's two members of Mt. Lebanon also made lined sewing boxes. They were made of gumwood and pine with a brown stain and varnish finish. Interestingly in the picture, one of the four has fingers pointed to the left, and the top two clearly have the main tack line under the handle, but the main tack line of the bottom box is definitely shifted to the right. (From Shaker Lands and Shaker Hands, Stephen Miller, page 125)

The Shakers did make regularly a small number of round boxes for use as spittoons in their communities. Spit boxes had an additional wood or metal rim at the top, and were partially filled with sawdust or shavings. (The Book of Shaker Furniture, John Kassay, page 19)

This picture of spit boxes is on page 114 of Shaker Style: Form, Function, and Furniture by Sharon Duncan Koomler. The tacks or pegs for the bottom are higher than on oval boxes, suggesting that the bottom in spit boxes is thicker.

As mentioned earlier, the Shakers used solid wood (usually eastern white pine) for their tops and bottoms. At that time, plywood was not available. Solid wood expands and contracts seasonally with changes in temperature and relative humidity. Quartersawn wood is the most stable lumber, but still moves seasonally. A 4% swing in moisture content will cause a 12” wide quartersawn eastern white pine board to move 1/32” on average. If the board moves more than average, and the summer moisture content became higher than typical, the oval box may be damaged.

Part of the band along the bottom finger is missing. This damage is quite likely the result of seasonal expansion of a solid wood bottom. (In the Shaker Tradition, Lesley Duvall and Sharon Duane Koomer, page 135)

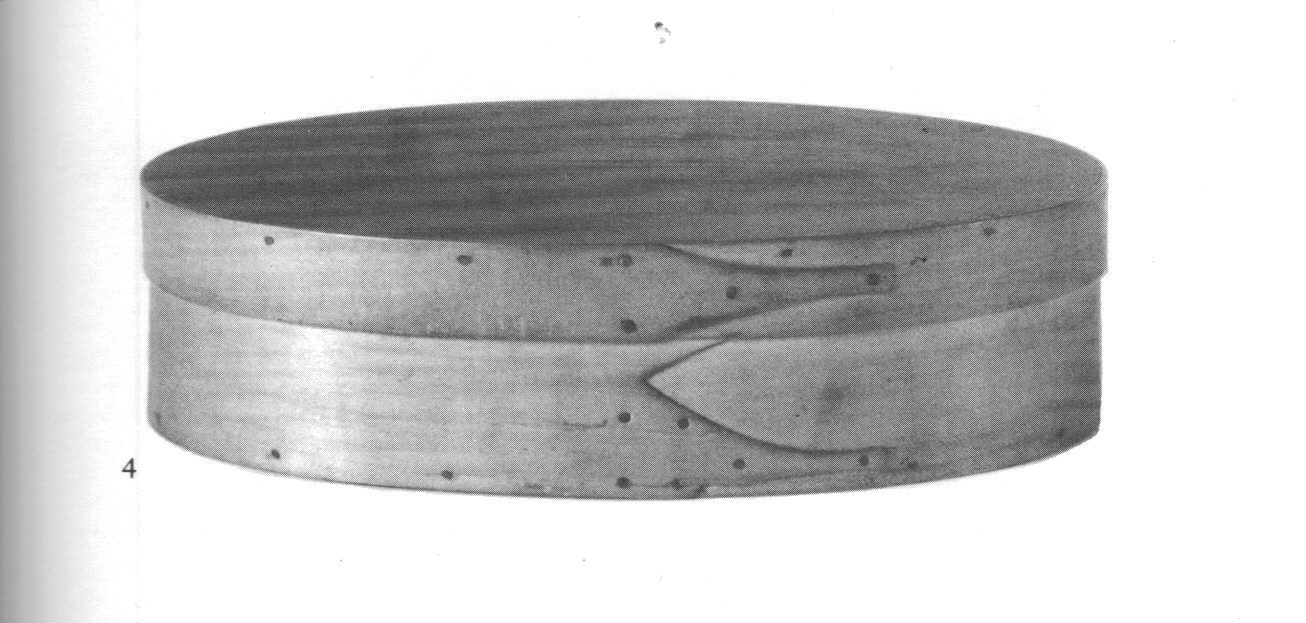

This picture from page 19 of The Book of Shaker Furniture by John Kassay shows an uncommonly shallow box attributed to New Lebanon, date unknown. The bottom edge of the bottom finger appears broken, and the bottom finger abbreviated. This may have been an existing box made shallower for a specific use, or an already shallow box whose band was damaged by seasonal expansion of a solid bottom.

Finally, this picture of a nest of painted blue oval boxes shows a broken band on the left edge of the lower left lid. (Shaker Style: Form, Function, and Furniture, Sharon Duncan Koomer) This damage also may have been due to seasonal expansion of a solid top.

Most Shaker-made oval boxes were a container and matching lid. In smaller numbers, they made containers with fixed handles, and oval boxes with swing handles. Several examples of fixed handle carriers were found, but only seven of swing handle carriers.

Like the boxes, handles were not identical. The most produced handle was that on the Sabbathday Lake swing handle sewing box shown earlier. It has small radius quarter circle corners and a flat middle section. Said to resemble the head covering worn by Shaker women, this pattern is often called a bonnet form. Although not found on Shaker-made boxes, one might wonder if an elliptical form would be more pleasing as a swing handle - it would parallel the shape of the lid. (This form however lacks a flat section where one's hand would grip the handle.) Finally, an arch form is between the two.

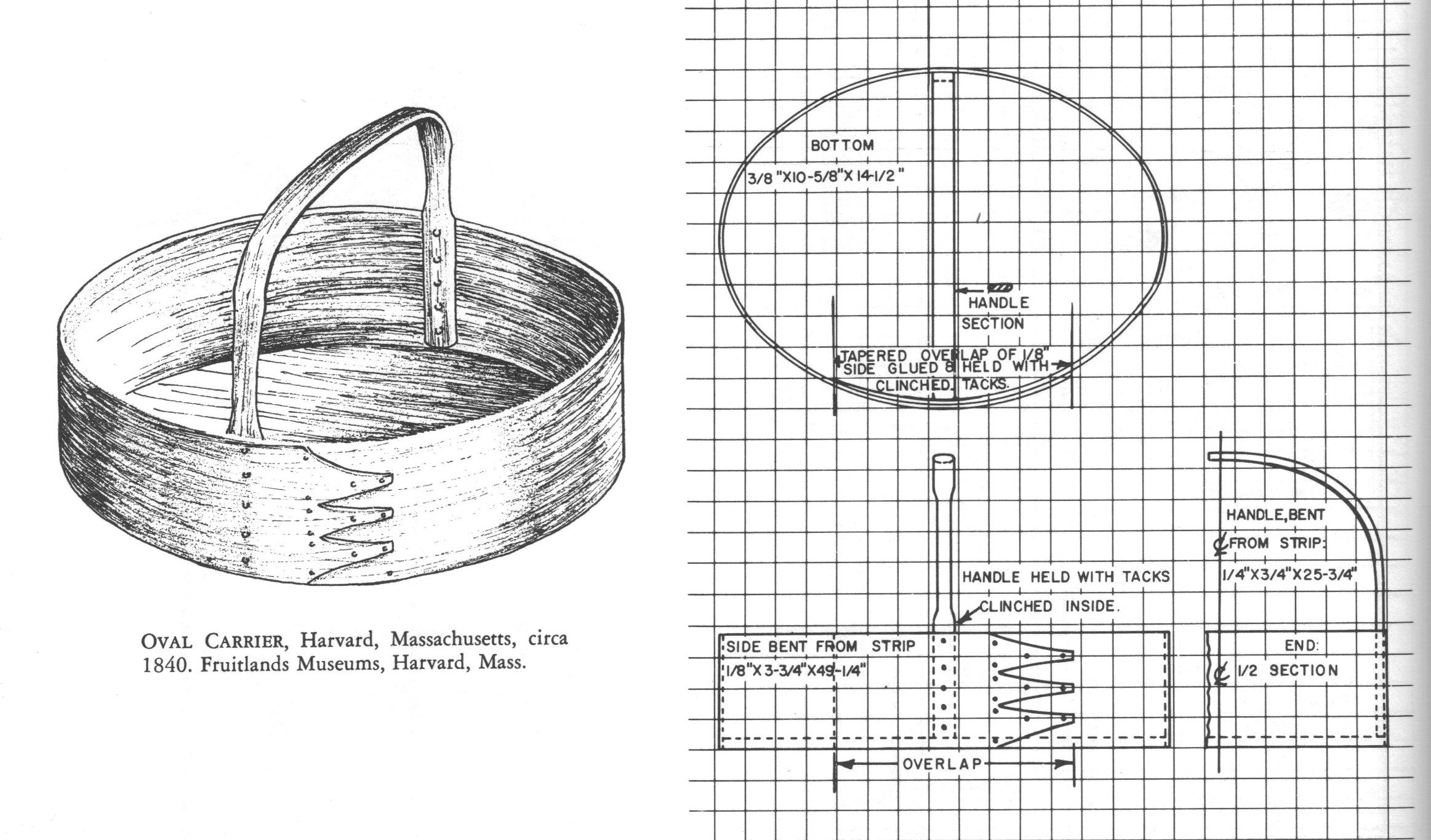

This drawing on page 112 of Making Authentic Shaker Furniture by John Shea is of a carrier attributed to Harvard, circa 1840. It shows a handle attached to the inside with a single row of tacks, with the handle uniformly narrowed between the top of the band and the top of the handle. The handle has an arch form. The main tack line is offset to the right from the minor axis almost two inches.

These three fixed handle carriers all have similarly trimmed handles - narrowed at the top of the container then tapering back in a straight line to full width. But the location of the main tack line is different in each. All three handles have a bonnet form - rounded corners and flat middle. And each handle is attached on each side with five tacks. The attribution of each is "probably Canterbury, 1840-1870." (The Essential Book of Shaker, David Larkin, page 45)

This photo shows a fixed handle brought out from the sides of the container with shims, so that the lid could still be used. This suggests the handle was added later. The main tack line is shifted to the right, suggesting the container was always intended to have a handle. There is a very large tack or even a rivet in the middle of the fixed handle, so perhaps the box originally was given a swing handle. (From Shaker Lands and Shaker Hands, Stephen Miller, page 122)

This picture from page 113 of Shaker Style: Form, Function, and Furniture, Sharon Duncan Koomler, shows both types of carrier.

The fixed handle carrier is the only Shaker-made oval box or container I’ve seen with the fingers pointing to the left. The handle is attached on each side with a four tack pattern, but the handle is trimmed like the three in the above picture. Finally, the handle has an arch form.

The swing handle in the picture is attached on top of the main tack line with a wooden strap and pivot. The handle is trimmed like the others but looks to have an elliptical or even round form. It's not known if the Shakers intended this swing handle carrier to have the pivot on top of the main tack line, or if the handle was added at a later time after the box was made.

Looking again at the Sabbathday Lake swing handle sewing carrier, the handle pivots on copper rivets, and has a more severe bonnet form. There is no trimming of the handle, resulting in a less refined look.

John Wilson

John Wilson has done much to raise awareness of the beauty and charm of handcrafted Shaker oval boxes.

Hired on short notice in 1980 to teach a woodworking class at Lansing Community College, he used Shop Drawings of Shaker Furniture and Woodenware Vol I by Ejner Handberg to suggest student projects. Intrigued by the book’s measured drawings of Shaker oval boxes, he found construction very challenging. An interpreter at the Hancock Shaker Village museum, Jerry Grant, shared techniques and tips. At about the same time John met a woodworker, Joel Kammeraad, who was making Shaker oval boxes and agreed to teach the process to that class.

John improved and refined his technique and instructional approach over the next two years as he taught Shaker oval boxes to his woodworking classes. In 1983 he also began teaching weekend workshops on Shaker box making, and continues to do so today.

Perhaps because he enjoys Shaker oval boxes so much, John has complemented the Handberg boxes by designing three smaller ones and fourteen larger ones, and a set of oval trays.

To facilitate those wishing to make Shaker oval boxes based on the Handberg drawings, John formed a company to sell instructional materials and all the supplies needed. John and his partner can be reached at www.shakerovalbox.com.

Return to Gift Ideas page

Return to Items For Sale page