Drawer Slips

There seems to be little historical information regarding drawer slips, so one can't say if the main purpose of slips was to extend the life or improve the proportion and look of a drawer. The distinction isn't important, because slips achieve both equally well, and deserve to be used in fine furniture.

Generally, drawer sides house a groove capturing the drawer bottom, said groove projecting about 1/4" into the drawer side. This groove weakens the drawer side, requiring that it be at least 1/2" thick. In graceful well detailed drawers this thickness looks heavy and out of touch with the rest of the piece of furniture.

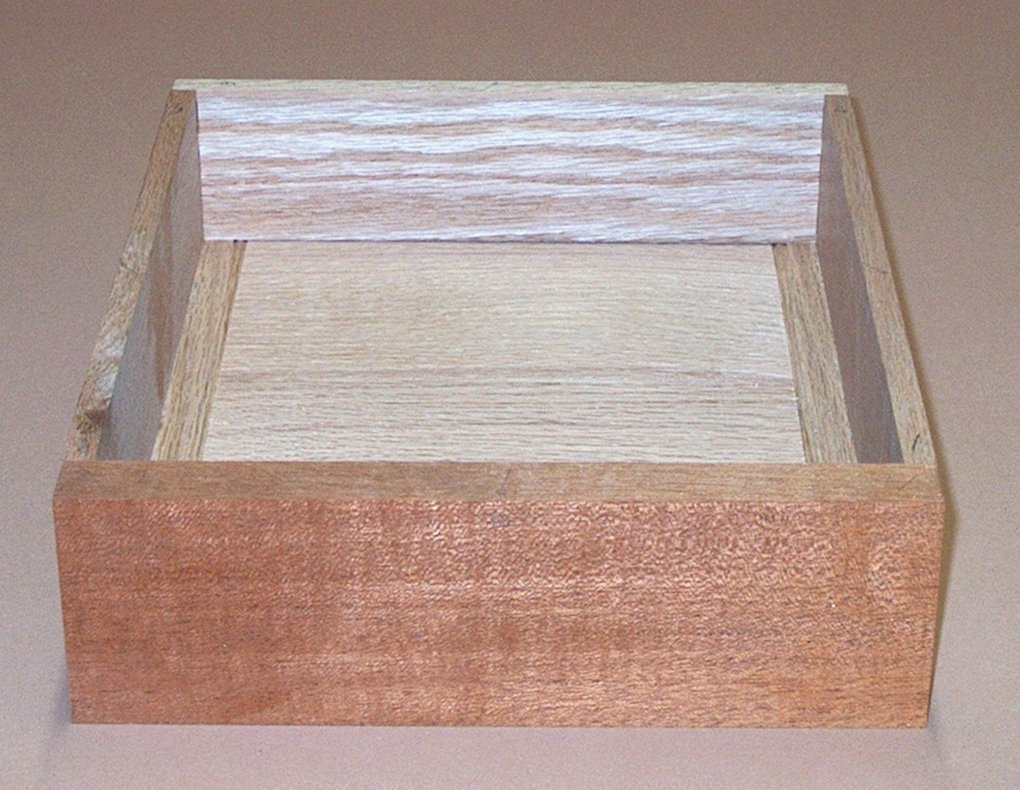

Perhaps one reason for the limited coverage in woodworking materials is that slips are a bit hard to explain. The picture at left shows side by side the outside back corner of two drawers. The one on the right is a traditional drawer with 1/2" thick side; the one on the left has a more graceful 3/8" thick side and a drawer slip.

Drawer slips were a feature of fine British furniture drawers of the 1700's and 1800's that unfortunately were not generally adapted by American furniture makers. One reference to "French drawers" showing slips suggests they may have also been used on the European continent.

Traditional fine furniture was always expected to last for generations. Drawers, a key component of fine furniture, were each made individually to fit their separate openings. During final fitting, the top and bottom of the drawer front, the top of the drawer sides, and the sides of the drawer sides were carefully planed to size. A well made drawer had an even gap around its front, and slid in and out with a minimum of play.

The drawers were supported by wood runners or bearers, and after thousands of openings and closings wear on the bottoms of the drawer sides and the surfaces of the runners became noticeable. This wear did not necessarily affect drawer use, but it did lower slightly the drawer in its opening. This lowering increased the gap over the drawer front, making the piece of furniture less attractive. A thin strip could be glued to the bottom of the drawer side, but repair of the drawer runner was more challenging.

The rate of wear can be decreased by widening the contact area. A 1" thick drawer side would accomplish this, but make the drawer much heavier, increasing the amount of friction between the drawer side and drawer runner. Such a thick drawer side also would be very unattractive. By simply widening the contact surface at the bottom of the drawer side, the slip significantly extended the amount of time before wear affected the fit of the drawer front in its opening. For the same reason, the rate of wear of the drawer runner was lessened.

Besides increased longevity, drawer slips make drawers visually lighter and more attractive. They add visual interest to the drawer interior. For several years, there has been a strong push in fine woodworking for narrow dovetail pins. Narrower pins are inherently weaker than wider ones, more prone to cracks and splits during fabrication, and aren't even seen when one opens a drawer. Unless the drawer bottom is covered with contents, drawer slips are immediately and prominently visible to the person opening the drawer.

There are two basic styles of drawer slip. One has its top even with the top of the drawer bottom and the other has its top higher than the surface of the drawer bottom.

This picture shows the interior and back of a drawer with a flush slip. Every example of a flush slip I've seen has a narrow scratch bead worked into the inner corner, as this one does. A narrow scratch bead adds tremendous interest and helps to hide the gap between the slip and the drawer bottom. (The camera flash makes the scratch bead hard to see.)

This picture shows the interior and back of a drawer with a quadrant slip. The slip extends above the drawer bottom about 1/4". The name likely is derived from its profile, a quarter or quadrant of a circle.

A third slip profile occasionally mentioned has a small cove in place of the roundover. No name was suggested for that profile, and no examples have been seen.

With all three types of slips, a groove is also worked into the back of the drawer front to receive the front edge of the drawer bottom. If a tenon is formed at the front end of the slips, it fits into the drawer front groove and helps align the slip as it is glued to the drawer side.

Wide drawers such a desk pencil drawer need intermediate support of the drawer bottom across its width. A flush center strip is let into the bottom of the drawer front and is screwed to the bottom of the drawer back. Grooves are worked into the two sides of this center strip for the two drawer bottoms. If the drawer has flush slips, it is expected that the same small bead would normally be worked into the two edges of this center strip. If the drawer has quadrant or cove slips, the center strip may remain flush without a scratch bead.

I am forever grateful to Mr. Richard Jones, Course Leader, Foundation Degree in Furniture Making, Leeds College, for introducing me to drawer slips many years ago with a posting on the Fine Woodworking forum. He has continued to share via that and other forums details and diagrams since that time. My additional primary source is The Essential Woodworker by Robert Wearing, expected to be published in mid 2010.

Birds mouth shelf supports, drawer slips, scratch beads - these are all examples of character-rich details lacking in modern mass-produced furniture.

Return to Best Traditional Woodworking Practices page